From slow motion running in Baywatch to slow motion walking on TikTok, filmmakers and social media creators alike have played with the suspension and stretching of time to achieve a particular “main character” moment.[1] However, with the latter this is more arduous as without special effects, movement must be intentionally slowed, the body tensed to control the smallest gestures.

The success of the slow walk tok[2] (a TikTok trend at its peak around late June to early July of 2020, in which people walk in place to Fkj and Masego’s “Tadow”) hinges on the impression of smooth, fluid movement. The aura of the main character moment this trend offers demonstrates the app’s potential as a personality building tool, wherein TikTok-specific features such as the Time Warp Scan filter are used to convey the grandeur and enigma of Renaissance painting.[3]

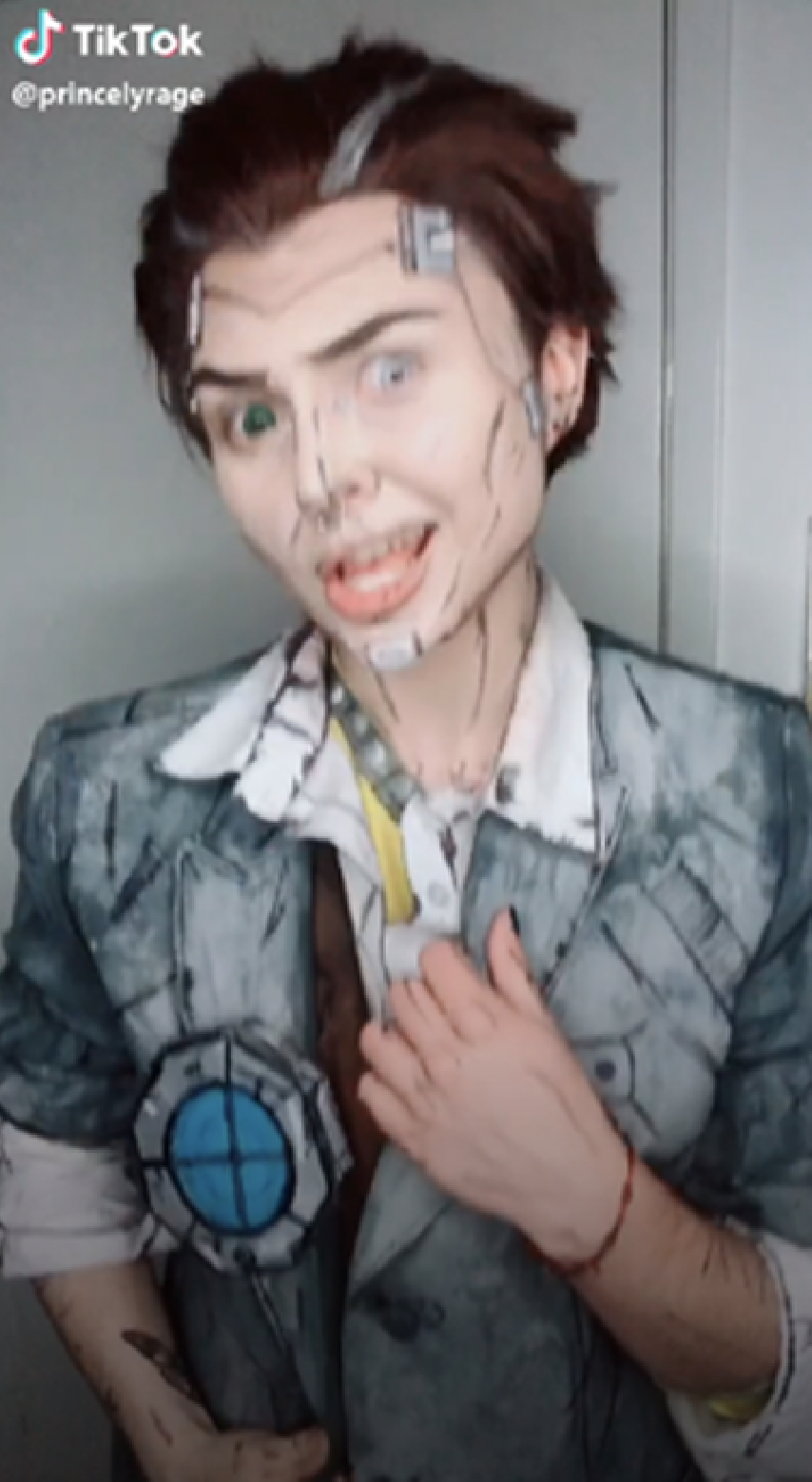

The slow walk trend bears resemblance to cosplay TikToks: in both of these the creator assumes the role of the protagonist, though in the former the character is a polished version of the self and in the latter, someone from a beloved franchise.[4] Cosplay toks are noted for the animatedness[5] of the character/creator, as well as their use of especially rhythmic music, often electro swing for its high energy.[6] Rather than the illusion of 4k hi-res cinematography, cosplay toks tend towards a supernatural verisimilitude where the body in all its three dimensionality is airbrushed, rotating and moving with an overly smooth flow and excessive easing reminiscent of AI-interpolated animation,[7] where the natural sharpness of certain gestures are spread out evenly.

As a cornerstone of the cosplay community on TikTok, the indie survival horror video

game turned media franchise Five Nights at Freddy’s (FNAF) has been massively influential on

tok making regardless of subculture and subject matter. Similar to Melanie Martinez’s music

videos (namely “Dollhouse”), the game’s theme of Frankenstein’s monster brought to life via

possessed animatronics — the melancholic puppet — establishes a tonal contrast that wrestles

with numerous dichotomies simultaneously: for instance, the good/bad, human/machine, and

gentle/violent.

An example of this is music group JT Machinima’s FNAF Sister Location song, “Join Us

For A Bite,” which serves as the audio to a TikTok trend[8] started by @keondra.k, in which they

lip sync to the song, adopting the robotic gestures of the FNAF animatronics.  The

composition of this video is a format widely used in cosplay toks, where the character/creator is

shown in a vertically stacked triptych (TikTok’s Triple Split Screen filter), which not only limits

the field of vision in each panel, but also adds a sense of uniformity and uncanniness through the

tripled selves, eerily synchronized and almost unbearably close.

The

composition of this video is a format widely used in cosplay toks, where the character/creator is

shown in a vertically stacked triptych (TikTok’s Triple Split Screen filter), which not only limits

the field of vision in each panel, but also adds a sense of uniformity and uncanniness through the

tripled selves, eerily synchronized and almost unbearably close.

This specific composition technique highlights the mobile device’s primacy as the frame of the

tok; the tall, narrowed bounds not only center the audience’s focus, but also guide the way

creators adapt to the limitations of the medium. Cosplayers may choose to visually flatten

themselves through the use of two dimensional makeup inspired by the bold, graphic linework so

often found in comic and manga illustration.  They may also choose to refrain from

leaning forward or backward — motion that may otherwise belie their “humanness” — to

maintain this optical illusion.

They may also choose to refrain from

leaning forward or backward — motion that may otherwise belie their “humanness” — to

maintain this optical illusion.

The unreal realness[9] to FNAF toks suggests a kind of distanced embodiment through a rejection of the weight of inhabiting a human body: much like popping, glitches and manual failures of the body are carefully controlled, so that even randomness is meticulously calculated. Through a mix of catchy, short (around 15 seconds) audio clips (often mashups that allow for a dramatic transformation to highlight the aforementioned emotional and thematic juxtapositions), bold transitions (through precise lighting, shots, and editing), and the character/creator’s own gestures, these cosplay toks immerse the viewer in a constructed world so rapidly that repeated viewing, enabled by TikTok’s automatic looping function, allows the audience to appreciate the effort and heart that went into its making.

As TikTok demographics consist of mostly young people (teenaged members of Generation Z), the app is fertile ground for meme[10] making. While internet informed[11] music videos such as Yung Lean’s “Hurt,” Doja Cat’s “Mooo!,” and Freddie Dredd’s “Witness” are self-reflexive in their art direction, they still can be taken seriously as the aesthetic of low fidelity enhances and reflects the music’s atmosphere. TikTok, however, struggles with gaining this authorial tone of voice: because its predecessor, Musical.ly, and similar social media apps such as Vine and Dubsmash are so closely intertwined with infamous memes, it is thus generally considered an informal medium,[12] which leads to an embedded memetic quality inherent to any video created with it.[13] Moreover, Gen Z’s penchant for chaos, situated in an American culture obsessed with transgression,[14] is expressed through tonal extremes in a tok’s audio: harsh, gritty music whose lyrics are often laced with aggression may perpetuate the romanticization of violence and abuse, which in turn might explain the plethora of mafia boss POVs (point of view roleplay videos) that echo mid 2010s “kidnapped by the alpha male” fiction. It is from these electronic, metallic, and densely textured songs (such as the upbeat yet dark chorus of “Join Us For A Bite”) that TikTok trends originate.

Fueled by the excitement of being innovators and early adopters of the latest TikTok

trends (no matter how niche they may be), Gen Z’s investment in a meme economy is evident in

comment sections, where the language is saturated with corporate undertones. .png?v=1622218198856) The

mechanics of social media engagement, a simulacrum in which virality and app-defined metrics

are unanimously taken as signifiers of merit and value — social capital — drive voracious media

consumption and shape the discourse around certain subcultures.

The

mechanics of social media engagement, a simulacrum in which virality and app-defined metrics

are unanimously taken as signifiers of merit and value — social capital — drive voracious media

consumption and shape the discourse around certain subcultures.

The spread of cosplay toks outside its immediate community can be traced to

Nyannyancosplay (also known as Kat), a cosplayer who popularized TikTok in a 2018 video[15]

where she lip synced to a portion of iLOVEFRiDAY’s diss track, “MiA KHALiFA.” After Kat’s

video there have been several app-wide trends created by cosplayers: an instance of this is

Anime Is An Important Part Of Our Culture, which refers to the audio of a 2019 tok  by

@tsun.bun — the track a mashup of a sound clip from Danganronpa 3: The End of Hope’s Peak

High School (a mystery horror anime TV series) and “nursery” by bbno$ and Lentra. The

meme’s evolution from its cosplay-specific context, where its audience would be familiar with

the dialogue, to the larger TikTok community (the main format of the #tremblechallenge[16]

defined by @witney8 a few weeks later) reflects the way context and specificity disappear as

audio tracks circulate in the app.

by

@tsun.bun — the track a mashup of a sound clip from Danganronpa 3: The End of Hope’s Peak

High School (a mystery horror anime TV series) and “nursery” by bbno$ and Lentra. The

meme’s evolution from its cosplay-specific context, where its audience would be familiar with

the dialogue, to the larger TikTok community (the main format of the #tremblechallenge[16]

defined by @witney8 a few weeks later) reflects the way context and specificity disappear as

audio tracks circulate in the app.

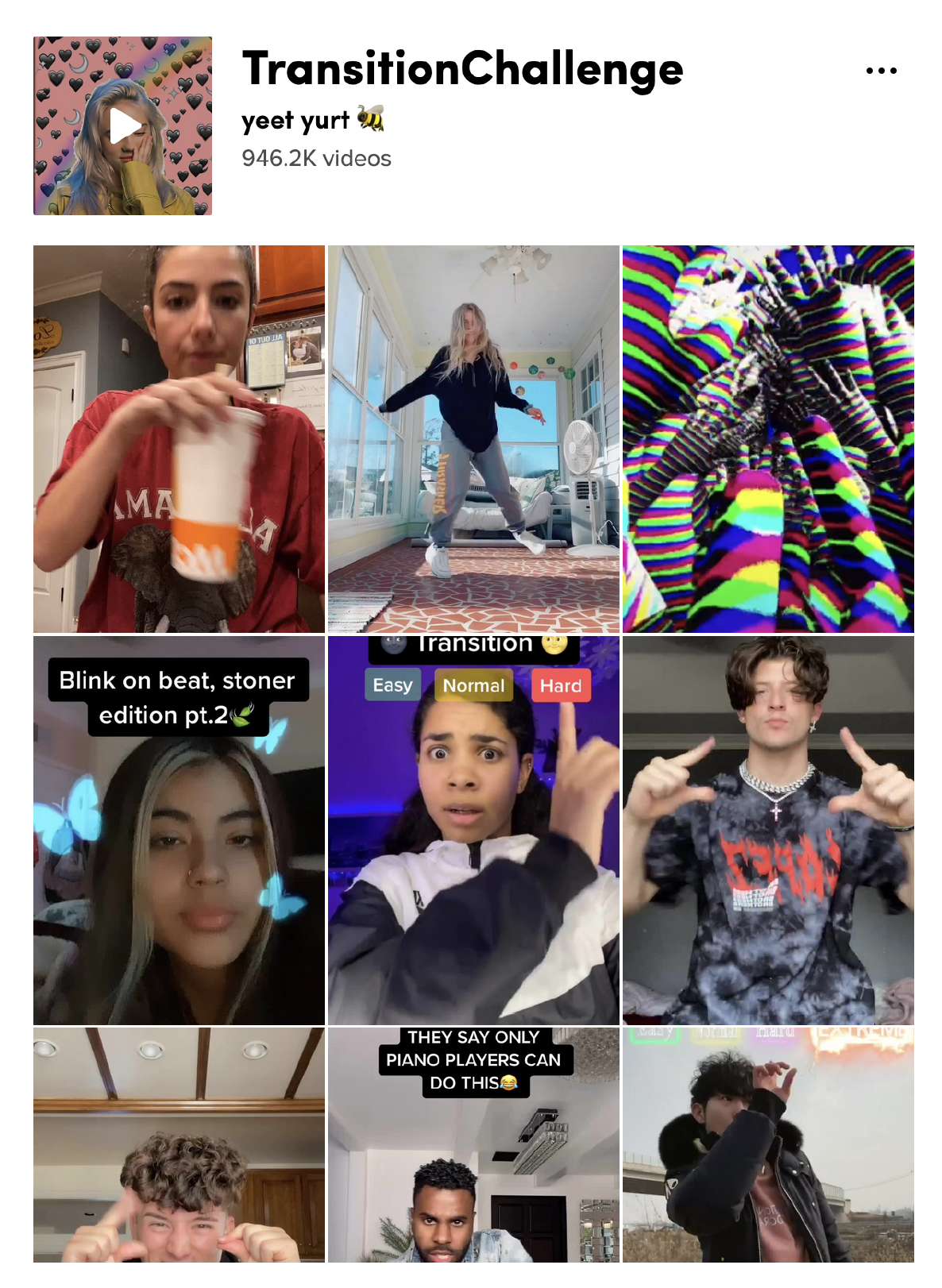

Beyond Anime Is An Important Part Of Our Culture, Danganronpa’s influence on

TikTok has led to the spread of Junko poses, hand signals of Junko Enoshima,[17] the main

antagonist of the TV series (whose voice appeared in the Anime Is An Important Part Of Our

Culture audio). The #junkoposingchallenge of summer 2018, in which cosplayers Junko pose

as precisely and quickly as possible  , later became the #transitionchallenge,

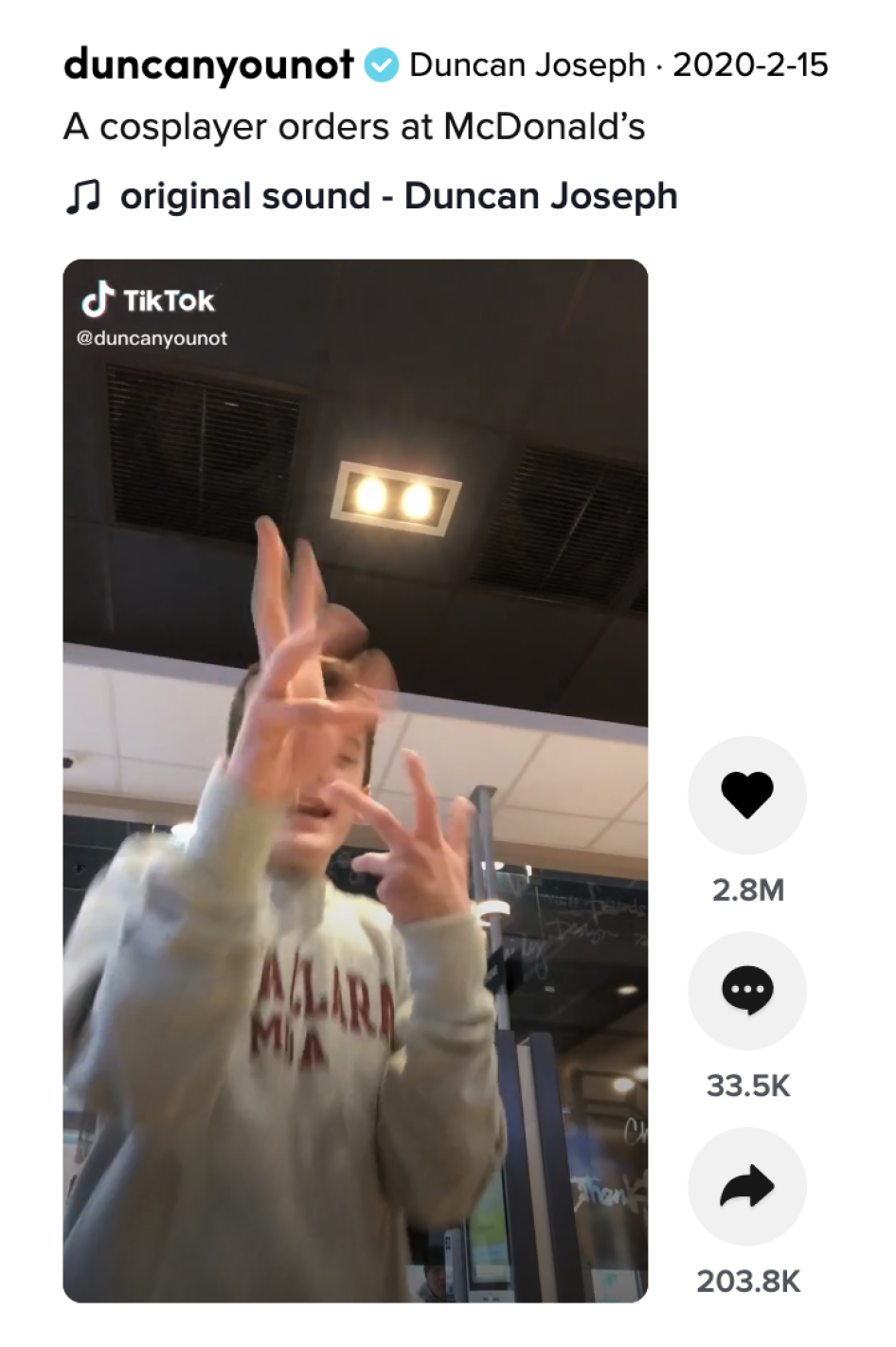

, later became the #transitionchallenge,  where people[18] blink or tap their fingers to the rhythm of the music. Other uses of the audio, such

as @duncanyounot’s (Duncan Joseph) videos[19] in which he does an impression of a stereotypical

cosplayer by Junko posing as he speaks, demonstrates the compression of the original meme,

which recalls the “flattening-out of visual content” Hito Steyerl discusses in “In Defense of the

Poor Image” —

where people[18] blink or tap their fingers to the rhythm of the music. Other uses of the audio, such

as @duncanyounot’s (Duncan Joseph) videos[19] in which he does an impression of a stereotypical

cosplayer by Junko posing as he speaks, demonstrates the compression of the original meme,

which recalls the “flattening-out of visual content” Hito Steyerl discusses in “In Defense of the

Poor Image” —

The compression at play in Joseph’s cosplayer series, wherein the most culturally specific elements of Junko posing are isolated and applied without regard to Danganronpa — so often the source material is lost[20] — turns the cosplayer identity into a meme that can be referenced by increasingly diluted hand gestures, devoid of all their original meaning.

Joseph has also created an iteration of the character in which the cosplayer identity

appears to be a repressed, undesirable trait — a trope similar to the hysterical woman — in

contrast to the otherwise “normal” and socially acceptable hot guy.

The animatedness of Joseph’s cosplayer adds a feeling of disgust and maybe even abjection, as if an

untamed, hidden alter ego acting out in public. In the “cosplayer’s order at McDonald’s”

scenario, Joseph also incorporates ethnic language such as “senpai soda” and “kawaii cookies,”[21]

which all the more entrenches the cosplay community in the stereotype of being hopelessly

infatuated with a foreign culture which they wholeheartedly embrace without any criticality.

The animatedness of Joseph’s cosplayer adds a feeling of disgust and maybe even abjection, as if an

untamed, hidden alter ego acting out in public. In the “cosplayer’s order at McDonald’s”

scenario, Joseph also incorporates ethnic language such as “senpai soda” and “kawaii cookies,”[21]

which all the more entrenches the cosplay community in the stereotype of being hopelessly

infatuated with a foreign culture which they wholeheartedly embrace without any criticality.

Perhaps the appeal of Joseph’s cosplayer bits are clear: they offer an easy and convenient

explanation into a lifestyle and subculture already so ridiculed (and critiqued, with good reason)

in mainstream American media; his audience presumably consists of mainland American teens.

However, the use of cosplayer gestures by @meltedtigerbalm may provide a more fruitful way to

engage with this meme format. By remaining fully in character and gliding to the cadence of the

sound, @meltedtigerbalm’s memes use tonal contradictions where gesture is not only an

interpretation but also an extension of the audio, animating the absurdist news story with a

deadpan seriousness.  Rather than situating the cosplayer as the other, these toks are

inviting, the punchline ultimately the audiovisual contrast.

Rather than situating the cosplayer as the other, these toks are

inviting, the punchline ultimately the audiovisual contrast.

The chief difference between Joseph and @meltedtigerbalm’s cosplayer series is thus the way this fundamentally unnatural[22] movement functions. As Jay Owens notes in “The Age of Post-Authenticity and the Ironic Truths of Meme Culture,” memes are “a kind of Trojan horse,” a mediating force that allows people to express some of their most vulnerable feelings through “irony and cultural quotation.” The proliferation of cosplayer gestures signals the inextricable ties between contemporary identity and both the social networks that ground it as well as the media that informs its expression. As a mode of escapism and aspirational identity formation, Junko posing transcends the norms of an American society that stresses sprezzatura[23] and “perfect imperfection,” daring to replicate the craft and aura of entertainment that may not be appropriate for the informal nature of TikTok.

Donna Haraway writes of the cyborg existence as one that is “outside salvation history,” one that rejects the Western myth of an “original unity.” As a performance of such a cyborg identity, cosplay takes on the terror of the unknown — bodily glitches, supernatural smoothness — and naturalizes it as a way to build on existing fictional canon, each person contributing through their own rendition of a character.

As the definitions of irony, sarcasm, satire, and dark humor are being reinterpreted and emphatically claimed daily by people who strive for an edgy persona, the cosplayer gesture meme feels cruel in its use of this identity as a mediating force to distance oneself from the uncomfortable. The meme — Steyerl’s poor image — while working against “the fetish value of high resolution,” is paradoxically “integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation.” Perhaps this is why successful memes are so visceral, even if they are cloaked with countless layers of reference and metacommentary, for that is all simply pure noise.

Evoking the impression of an identity only to outsource it as a mode of emotional labor (whether it’s the lurking sensation of not being cool enough — of being cringe, or an avoidance of ideological conflict), as trivial and minute as this may seem, can be exploitative. Giorgio Agamben writes, “an era that has lost its gestures is, for that very reason, obsessed with them; for people who are bereft of all that is natural to them, every gesture becomes a fate.” While cosplayer gestures are not so clearly racialized or gendered,[24] their use calls to mind those that have been detached from their original contexts. In Notes on Gesture, Martine Syms highlights the specificity of such movement that, once intimately tied to the subjectivity of Black womanhood, do not appear as neutral as Whiteness may now claim; as Lauren Michele Jackson writes, “no digital behavior exists in a deracialized vacuum.” The spread of other gestures such as the Woah, the Whip, the Dab, and the Ice In My Veins pose[25] (which is sadly also known as “the TikTok Arm Thing”) across social media parallels the misuse of African American Vernacular English: at what cost does relevance come when the expression of the self is contingent on the use of Black culture — as well as drag culture — as a prop?

In an age of mechanical reproduction, endless remixing, and infinitely nested memes, perhaps there are ways to participate in cultural production through interventions into the otherwise flat landscape. Gestures from cosplay TikTok may serve as a noteworthy lesson in modes of embodiment, self expression, and connection.

Notes

1. Wherein the camera lens is focused on a specific person — this takes the form of the slow motion entrance, where the (camera’s voyeuristic) gaze slowly tracks up across the character’s body to their face. While Baywatch isn’t the first instance of this in film, I use it here as a general reference.

2. Individual TikTok videos hereafter abbreviated as tok.

3. The most notable Time Warp Scan trend is the angel/demon tok where the filter itself becomes a transformative tool: the transfiguration of people into mythic creatures is set to a slowed version of MGMT’s “Little Dark Age.” The trend might benefit from closer analysis as it signals a larger cultural longing for a primordial pathos.

4. People who cosplay (“costume (role)play”) are cosplayers; source material may be video games, anime, manga, comics and cartoons, television series, or book series.

5. Sianne Ngai defines “animatedness” in Ugly Feelings as an emotional affect that renders Black people as both “excessively ‘lively’” and “a pliant body unusually susceptible to external control.” In this essay I use animatedness to refer to the physical embodiment of an animated character, where a “puppet-like state” is desired, its political implications unexplored. Ngai’s analysis is similar to the exaggerated facial expressions favored by “Vine comedy” creators such as Lele Pons and on TikTok, Gil Croes.

6. See Charlie Puth’s Betty Boop remix for an example of an early and widely used swing influenced audio.

7. See Noodle, “Smoother animation ≠ Better animation [4K 60FPS]” for a video essay about the (mis)use of interpolation in animation.

8. @keondra.k’s tok has gained nearly 700 thousand likes, though the most widespread version of their format, by @caleb.finn has accrued 2.5 million likes. The audio itself has been used by 870,000 + videos.

9. Here I use realness as a synonym for “verisimilitude” — rather than its definition in its queer and trans context.

10. Meme as in internet meme.

11. These works are internet informed in the sense that they feel lofi and may have an underlying sense of nostalgia for connection characteristic of Web 1.0; music videos often incorporate interface aesthetics, their facture (perhaps a nonchalance towards the level of polish as evident in spotty chroma key, for example) impacting larger cultural notions of authenticity and identity.

12. Just as the shift from YouTuber to mainstream celebrity is likewise difficult.

13. An analysis of social media app watermarks and similar symbols baked into videos created with free software may be fruitful to this discussion.

14. Discussed in the Media Education Foundation’s 1997 interview with bell hooks on cultural criticism and transformation.

15. Kat’s tok has amassed around 550,000 likes and launched several memes; the original video also has become a trend to imitate, as well as its lyrics shouted in public places (during the fall/winter of 2018) as a code to identify others who also use TikTok.

16. See variations in this YouTube compilation — the visual/performative structure of the meme loosens and the only way to reliably refer to the meme is the soundbite, taken out of context.

17. See this Junko Enoshima compilation for her portrayal in the series and this Junko pose compilation for comparison — the audio of the latter also spreading beyond the Danganronpa fandom on TikTok.

18. From “straight TikTok” — a term used to describe more mainstream influencers and TikTok personalities, such as Charli D’Amelio. Straight presumably meaning heteronormative. The “straight TikTok” v. “alt (alternative) TikTok” divide has been likened to the way Tumblr was described as having different “sides.”

19. See  “Cosplayers if they needed to save someone’s heart” for the most viewed video of this series; the cosplayer character toks are not listed as a formal series,

though Joseph’s “Karen” and “Sim” videos are.

“Cosplayers if they needed to save someone’s heart” for the most viewed video of this series; the cosplayer character toks are not listed as a formal series,

though Joseph’s “Karen” and “Sim” videos are.

20. Perhaps tracking TikTok trends and memes demonstrates not only the flow of communication and exchange, but also highlights the weaknesses of the app’s design. Audio tracks can be downloaded and reuploaded as one’s own, a strategy used by many who have stolen content. The “inspired by” ib credit, which is customarily in the caption, may be instead commented. Intellectual property, ownership, authorship, etc. are important topics to discuss as they relate to TikTok’s app architecture.

21. This phrasing is similar to Ashnikko’s “Slumber Party,” the lyrics of which include “she cute, kawaii, hentai boobies, that excites me” — while the impact of Japanese cultural exports such as entertainment (amidst so many other fields) is too complex to discuss in this essay, I do want to note the way America (i.e. the West) interacts with Japan and ask whether the latter also plays a part in perpetuating certain harmful ideologies, especially as they relate to gender, sexuality, and race.

22. As cosplay toks proper aspire to be — animatedness strives for a cartoon-like realness/naturalness.

23. Studied nonchalance, the messy bun — see morning routine YouTube videos, which have changed from a perfect, idyllic tone (e.g. common traits may involve an early bird schedule, an emphasis on productivity, [physical] fitness — often quite gendered) to one that’s more carefree, looser and not as rigid (i.e., see the ever-shifting definition of relatability on YouTube).

24. Another connection here is the stereotypical portrayal of gay men in which traditionally effeminate gestures are the punchline of humor rooted in homophobia and misogyny.

25. See @kahlilgreene’s TikTok series, “How Everything on This App Originated with Black People (Episode 1).”

References

Jay Owens, “Post-Authenticity and the Ironic Truths of Meme Culture.” Medium. Medium, August 15, 2018.

Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.” e-flux. Nov, 2009.

Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” Socialist Review, 1985.

Giorgio Agamben, Infancy and History: the Destruction of Experience. London: Verso, 2007.

Martine Syms, Notes on Gesture. 2015.

Lauren Michele Jackson, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs.” Teen Vogue, August 2, 2017.